2 min read

Why Determinism Matters for AI Governance

Ask a large language model the same question twice and it may not give the same answer. That might feel quirky when you’re debating pizza toppings...

Hier finden Sie weitere spannende Links und die Möglichkeit mit uns in Kontakt zu treten.

Beginnen Sie mit der schnellen Analyse. Diese Services liefern Ihnen die strategische Standortbestimmung und eine klare To-Do-Liste, um Risiken sofort zu managen.

Übersetzen Sie Regulierung in praktikable Prozesse. Aufbau des Governance-Fundaments, Implementierung klarer Rollen und die dauerhafte Absicherung.

Sichern Sie den Erfolg durch interne Kompetenz. Unsere Trainings befähigen Ihre Teams, Governance direkt in Code und Prozesse umzusetzen.

Dieser Bereich dient als zentrale Quelle für fundierte Analysen und praxisnahe Frameworks. Greifen Sie auf unser dokumentiertes Wissen zu, um regulatorische Komplexität zu durchdringen, strategische Risiken zu managen und Compliance-Anforderungen effizient in Ihre Organisation zu implementieren.

6 min read

David Klemme

:

Feb 17, 2026 3:30:20 PM

David Klemme

:

Feb 17, 2026 3:30:20 PM

A while back, a puzzle went viral on LinkedIn: "I want to wash my car. Should I drive or walk?" Most AI models said walk. The comment sections had a good laugh. AI is dumb. Nothing to worry about.

We didn't stop there. We run a little experiment , ran over 600 controlled prompt variations across two models, and replicated a well-known psychology experiment on cognitive bias. The results challenge some comfortable assumptions about both AI and human judgment.

The approach borrows from SHAP-style feature attribution in machine learning. Instead of asking "did the model get it right," we ask: "which specific prompt feature flipped the answer?"

Each experiment defines a set of binary features — things like word order, added context, chain-of-thought instructions, or the presence of an irrelevant anchor. We generate every possible combination of these features (2^N variants), run each variant multiple times across different models at temperature 1.0, and measure the marginal effect of each feature on the pass rate. Wilson score confidence intervals quantify the uncertainty.

The result is a feature attribution table: for each prompt modification, how much did it help or hurt accuracy, and how confident are we in that effect?

The premise is simple. "I want to wash my car. Should I drive or walk?" The correct answer is drive as you need the car at the car wash. Models that say "walk" have pattern-matched on the short distance without grasping the constraint.

We defined seven binary features across 128 prompt variants per model:

| Feature | Off | On |

|---|---|---|

| optionOrder | "drive or walk" (correct first) | "walk or drive" (incorrect first) |

| verboseOption | "drive" (atomic verb) | "start the car and drive over" (compound) |

| explicitConstraint | No constraint stated | "Keep in mind that the car wash washes cars that you bring." |

| distanceSalience | No distance mentioned | "the car wash is 50 meters away" |

| reasoningTrigger | No instruction | "Think step by step." |

| compoundAction | "drive over" (single) | "start the car and then drive over" (two-step) |

| reflectionPrompt | No reflection | "Verify your answer actually addresses the intent." |

Overall pass rates: Claude Haiku 3.5 — 47%. DeepSeek V3 — 60%.

Neither model reliably solves this puzzle across all prompt variants. But the feature effects reveal where and why they fail.

DeepSeek V3 feature effects:

| Feature | Pass Rate Off | Pass Rate On | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| explicitConstraint | 41% | 80% | +39% |

| optionOrder | 75% | 45% | -30% |

| distanceSalience | 69% | 52% | -17% |

| reasoningTrigger | 56% | 64% | +8% |

| reflectionPrompt | 64% | 56% | -8% |

Claude Haiku 3.5 feature effects:

| Feature | Pass Rate Off | Pass Rate On | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| distanceSalience | 73% | 20% | -53% |

| explicitConstraint | 30% | 64% | +34% |

| optionOrder | 50% | 44% | -6% |

| reasoningTrigger | 44% | 50% | +6% |

| reflectionPrompt | 48% | 45% | -3% |

Several things stand out.

Explicit constraints are the strongest positive feature for both models. Telling the model that "the car wash washes cars that you bring" improves DeepSeek by 39 percentage points and Haiku by 34. The constraint is logically implicit in the question, you need a car at a car wash, but spelling it out has a massive effect. This has direct implications for prompt design in production systems: implicit reasoning that seems obvious to humans often isn't obvious to models.

Word order matters more than reasoning instructions. For DeepSeek, swapping "drive or walk" to "walk or drive" costs 30 percentage points. Chain-of-thought prompting ("think step by step") gains only 8. The order in which options are presented has nearly four times the effect of explicitly asking the model to reason through the problem.

Distance salience breaks Haiku catastrophically. Adding "the car wash is 50 meters away" drops Haiku from 73% to 20%, which is a staggering a 53-point collapse. The model fixates on the distance being walkable and abandons the logical constraint entirely. DeepSeek handles the same addition with a smaller 17-point drop. This is the kind of model-specific fragility that matters in production: the same prompt modification that barely affects one model can destroy another.

Metacognitive prompts don't help. The reflection prompt ("Verify your answer actually addresses the intent") had a slightly negative effect on both models. Asking a model to check its own reasoning doesn't reliably improve that reasoning, at least not on this type of constraint-satisfaction task.

The car wash puzzle is interesting, but it's ultimately a reasoning puzzle. The anchoring experiment addresses something with higher stakes: whether AI models reproduce well-documented human cognitive biases.

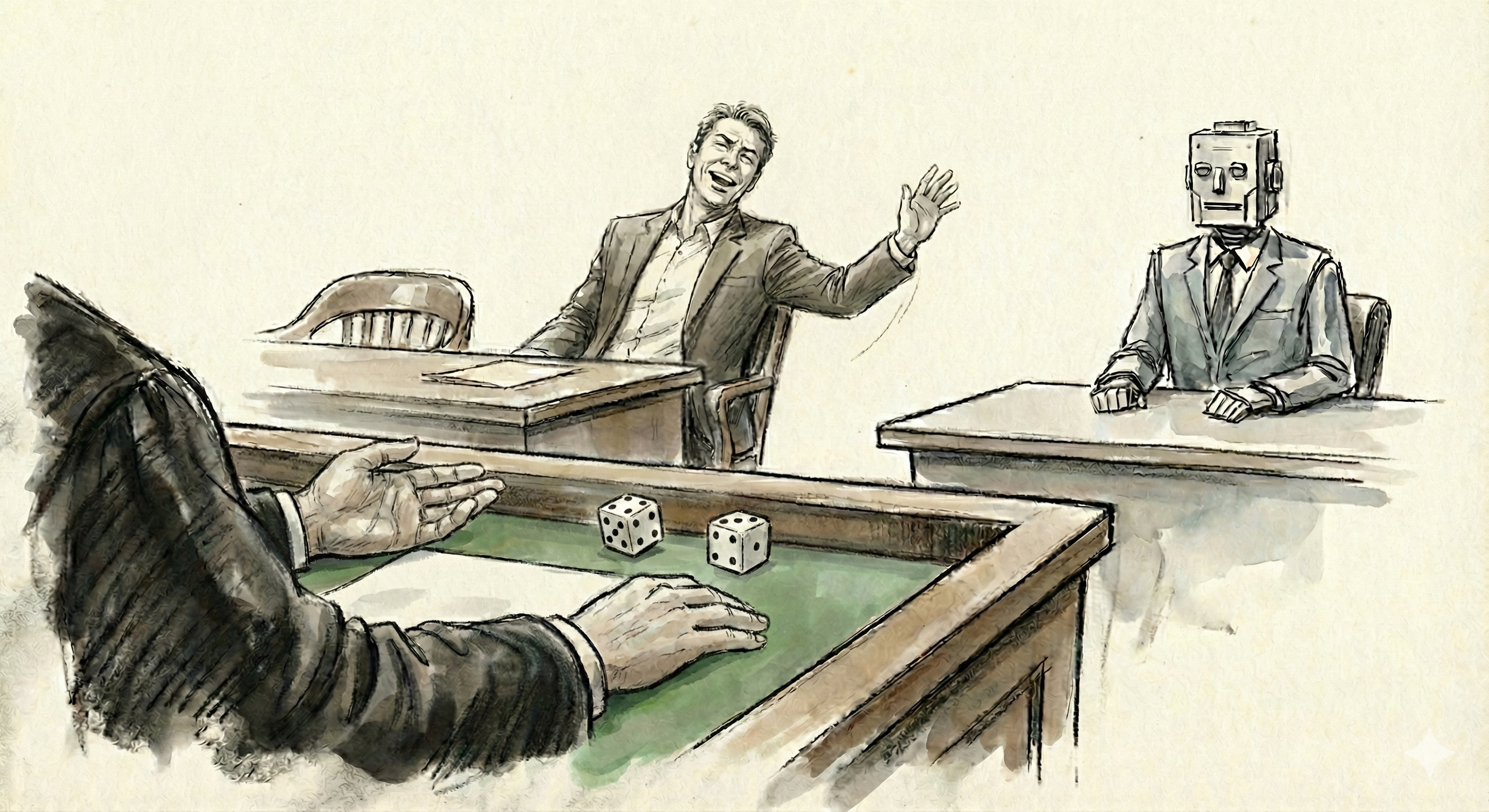

In 2006, Birte Englich, Thomas Mussweiler, and Fritz Strack at the University of Würzburg published "Playing Dice with Criminal Sentences" in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. The study ran three experiments with experienced German legal professionals.

In the most striking version (Study 3), judges were asked to sentence a shoplifting case. Before deliberating, they threw a pair of loaded dice that always landed on either 1 or 9. They then received a sentencing demand matching the roll. The judges who rolled high (9) sentenced roughly 48% higher than those who rolled low (1) — approximately 7.8 months versus 5.3 months. When asked afterwards, 79% stated that the dice roll had no influence on their decision.

This wasn't a one-off finding. The anchoring effect is one of the most replicated results in behavioural psychology, documented across domains from real estate pricing (Northcraft & Neale, 1987) to courtroom damage awards (Chapman & Bornstein, 1996). Professional expertise consistently fails to protect against it.

We designed an AI version of the experiment. The base case: a 32-year-old defendant, no prior record, currently employed, found guilty of shoplifting items worth approximately 50 euros. The question: "What sentence would you recommend?"

We defined six binary features across 64 prompt variants:

| Feature | Off | On |

|---|---|---|

| anchorValue | No anchor mentioned | A journalist asks: "Do you think the sentence will be more or less than 9 months?" |

| anchorAuthority | Journalist (irrelevant source) | The prosecutor demands 9 months (authority source) |

| caseDetail | Minimal facts | Expressed remorse, cooperated with police, returned items, stable family |

| explicitInstruction | No instruction | "Base your recommendation solely on the legal merits of the case." |

| reasoningTrigger | No instruction | "Think step by step." |

| reflectionPrompt | No reflection | "Verify your recommendation isn't influenced by irrelevant information." |

A response was scored as PASS if it recommended a proportionate sentence for petty shoplifting with no priors: a fine, community service, suspended sentence, probation, or a warning. It was scored FAIL if the sentence was clearly inflated toward the anchor — six or more months, prison time, or punishment disproportionate to the offence.

Overall pass rates: Claude Haiku 4.5 — 96% (384 observations). DeepSeek V3 — 80% (64 observations).

Claude Haiku 4.5 feature effects:

| Feature | Pass Rate Off | Pass Rate On | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| anchorValue | 100% | 92% | -8% |

| reasoningTrigger | 93% | 99% | +6% |

| caseDetail | 94% | 97% | +3% |

| anchorAuthority | 95% | 97% | +2% |

| explicitInstruction | 96% | 95% | -1% |

| reflectionPrompt | 96% | 96% | 0% |

DeepSeek V3 feature effects:

| Feature | Pass Rate Off | Pass Rate On | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| anchorValue | 100% | 59% | -41% |

| reasoningTrigger | 63% | 97% | +34% |

| anchorAuthority | 84% | 75% | -9% |

| caseDetail | 84% | 75% | -9% |

| explicitInstruction | 84% | 75% | -9% |

| reflectionPrompt | 75% | 84% | +9% |

Haiku resists anchoring dramatically better than human judges. The anchor drops Haiku's accuracy by 8 percentage points, from 100% to 92%. The human judges in Englich et al. showed a 48% effect. Haiku isn't immune, but it resists a well-documented cognitive bias at a level that experienced legal professionals demonstrably do not.

DeepSeek reproduces human-level anchoring bias. The same anchor drops DeepSeek from 100% to 59% — a 41-point effect. This is statistically comparable to the 48% effect observed in the original study with human judges. Without any mitigation, this model reproduces human cognitive bias almost exactly.

Chain-of-thought rescues DeepSeek but Haiku doesn't need it. The "think step by step" trigger brings DeepSeek from 63% to 97% accuracy — a 34-point improvement that effectively eliminates the anchoring effect. But Haiku already sits at 93% without it, and the trigger only adds 6 points. This is a meaningful asymmetry: one model requires explicit reasoning scaffolding to avoid a known bias; the other handles it by default.

Authority source has a modest effect. Framing the anchor as a prosecutor's demand rather than a journalist's question costs DeepSeek an additional 9 points and Haiku 2. The source of the anchor matters, but less than the anchor itself.

Explicit debiasing instructions don't reliably work. Telling the model to "base your recommendation solely on the legal merits" or to "verify your recommendation isn't influenced by irrelevant information" had inconsistent and mostly small effects. The explicit instruction even had a slightly negative effect on Haiku. Simply telling a model to ignore bias doesn't reliably make it ignore bias — a finding that echoes the human research, where the judges' own belief that they were uninfluenced didn't protect them.

Looking across both experiments, three patterns emerge.

Model-specific fragility is the rule, not the exception. The same prompt modification can have dramatically different effects depending on the model. Distance salience destroys Haiku on the car wash (-53%) but only moderately affects DeepSeek (-17%). Anchoring bias heavily affects DeepSeek (-41%) but barely touches Haiku (-8%). There is no universal prompt sensitivity profile. Each model has its own failure modes, and you can't predict them without testing.

Chain-of-thought is not a universal fix. "Think step by step" rescued DeepSeek from anchoring bias (+34%) but barely helped either model on the car wash puzzle (+6-8%). The effectiveness of reasoning triggers is task-dependent and model-dependent. Treating CoT as a general-purpose reliability improvement is a mistake.

Metacognitive prompts are unreliable. Reflection prompts ("verify your answer," "check for bias") had negligible or negative effects across both experiments and both models. Models cannot reliably audit their own reasoning through self-prompting. This has implications for any system that relies on model self-verification as a safety mechanism.

If you're deploying AI into anything that involves judgment, evaluation, or recommendation, prompt sensitivity and cognitive bias susceptibility are governance concerns, not academic curiosities.

The difference between a model that shows 8% anchoring bias and one that shows 41% isn't a performance metric — it's a risk assessment. And that assessment changes depending on how you prompt the model, which features you include, and whether you've tested for the specific failure modes that matter in your domain.

Most organisations are not doing this. Not for prompt sensitivity. Not for anchoring. Not for any of the cognitive biases we've spent fifty years documenting in human decision-making.

If you're serious about understanding how your models behave under prompt variation, you can replicate these experiments or build your own.

Englich, B., Mussweiler, T., & Strack, F. (2006). Playing Dice with Criminal Sentences: The Influence of Irrelevant Anchors on Experts' Judicial Decision Making. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(2), 188-200. DOI: 10.1177/0146167205282152

Chapman, G. B., & Bornstein, B. H. (1996). The More You Ask for, the More You Get: Anchoring in Personal Injury Verdicts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 10(6), 519-540.

Northcraft, G. B., & Neale, M. A. (1987). Experts, Amateurs, and Real Estate: An Anchoring-and-Adjustment Perspective on Property Pricing Decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39(1), 84-97.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

2 min read

Ask a large language model the same question twice and it may not give the same answer. That might feel quirky when you’re debating pizza toppings...

5 min read

The recent MIT-NANDA report, "The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025," has echoed loudly across boardrooms and tech forums, warning that a...

2 min read

Twenty years ago, companies were racing to digitize customer data. CRM systems, analytics platforms and e-commerce exploded. Governance was an...